- Last Update: October 17, 2024

- Key Takeaways

- In the 2000s, domestic recycling became an unconscious act.

- Recycling rates more than tripled through the 2000s, from 12% to 39%.

- Throughout the 2000s more landfills closed than opened.

Recycling In The 2000s

In this series of articles, we have been looking at recycling through the ages, considering the changes in mentalities and behaviours, the environmental savings, and the comparative costs. This week we will be completing our recycling through the ages series with the 2000’s.

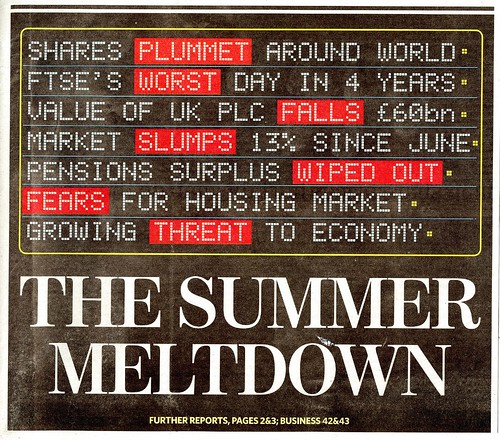

The Noughties, as they are commonly known, may seem a distant memory, but in the grand scheme on the universe, they were just a whisper away. Between 2000 and 2009, the world was a volatile place, with a war over oil, the resurrection of former republics, a modern day economic depression and the loss of the king of pop. Recycling had grown and blossomed during the past few decades, and was now fully prepared to enter a new millennium with the mission of invading every home and becoming the daily norm.

The 2000 Markets

Before the markets crashed, we were experiencing what is sometimes referred to as ‘the commodities super cycle’, a boom in the demand for physical commodities, like minerals, fuel, food and chemicals. This was all going rather swimmingly until the price of oil became unstable and began flying around like a pinball. If you’ll consider that in 2003, a barrel of oil cost just $30, and in 2008 it would have cost around $145, you can begin to see the instability. Today (August 2014), oil sits at a nine-month low of around $101. It’s still not stable. What does oil have to do with recycling though?

Manufacturing plastic products from virgin polymers (new plastic) is a far more energy reliant, oil driven and expensive procedure than using recycled plastic. Add in the fact that oil prices quadrupled, the benefit of recycling plastic became apparent and necessary, and around this time, around 2008, the industrial side of recycling really got a kick-start.

Recycled paper was about as volatile as oil, if not more so.

Here in the UK, recycled paper floored at a surprising low of just £10 per tonne in March 2009, a stark comparison to the year before when prices had been as much as £120 per tonne. Even today, the prices constantly change, but they haven’t been as low or high as these figures since the market crash. The £10 per tonne figure was attributed to an east Asia market crash that led to a non-demand for waste paper.

Recycling In The Home

Recycling bins have been described as ‘a British icon’ in the home, and it must be admitted, that’s an apt description. You’d be hard pressed to find British homes that actively oppose recycling (and nigh on impossible to find any with a valid reason) as in the 2000s, domestic recycling became an unconscious act. The government provided us with different coloured boxes and bins, and it became harder work to avoid using them, and would potentially arouse some sort of guilt born from ignorance.

Three flowing folding arrows, the universal symbol of recycling today, became synonymous with all generations during the Noughties. Governments funded recycling education in schools, and initiatives to encourage parents to set a good example. I fondly remember a school trip to a recycling centre as a child of no more than 10 years old. Thanks to these government schemes, and several that encouraged businesses to recycle more (including landfill closures and price hikes), recycling rates more than tripled through the 2000s, from 12% to 39%. Within that figure, the British domestic household rates increased from 11% to 43%, and that deserves a pat on the back. Wales ended 2009 as the best recycler of the home nations with 54% of domestic waste recycled. Even in 2014, Wales remains at the top, being the first to implement a charge for plastic bags in shops, reducing the use of the carrier bags by around 80%. I often see on recycling forums the glee and pride of the Welsh people at dominating this statistic.

Did you know: Household and business recycling rates combined increased from 42% in 2002 to 52% in 2010?

Recycling Forum Thoughts From 2007

I’ve taken a few quotes here from a 2007 forum discussing feelings about recycling, I hope you will agree that these attitudes were mostly commonplace during the Noughties (and still today).

‘I always recycle. Sometimes I will even go out of my way just to recycle something I have and am nowhere near a recycle bin at the time .’

‘When I bought my house, I asked the owner “where is the recycle container?” and he said that he never recycled, he did not have the time. What a pig. What extra time can it take? You throw the bottle or can into a different trash bin, that’s all. ‘

‘I recycle whatever I can – bottles, cans, paper, newspaper, cardboard, etc. I do what I can, but we as a society have a long, long way to go!’

‘I try to recycle as much as I can, but do inevitably end up throwing stuff out that could probably be recycled. I don’t think it’s possible for someone to recycle 100% of what they can…..well, it probably is, but they’d be carrying a ton of crap with them wherever they went.’

Domestic recycling was not seen as honourable or duteous, but just something that had to be done, as it didn’t make sense to avoid it. Let’s be honest, many of us were guilty of not recycling ‘on-the-go’, as it could be inconvenient and there wasn’t a recycling bin there when we needed one. Well in the late 2000s, the government began installing recycling bins next to general waste bins. Alternatively, they installed multi-bins that had different chutes for paper, drinks cans, plastic bottles and general waste, as well as compartments for cigarette butts and chewing gum. Current day, these are very common, and will be seen on any given high street.

Landfill Changes In The 2000s

When a landfill is full or no longer needed, it is often covered over, left for a few years and then built upon. The main problem with building on top of a landfill is that unstable material beneath the ground, causing car parks to dip and rise. I’ve seen an ex-landfill turned retail park recently where rain collects in various craters all over the site that exiting cars have to work hard to avoid. There’s also the issue of methane build-ups, but these are dealt with well by professionals.

In the ‘Government review of Waste Policy in 2011’ (not the Noughties, but talking about them), it is stated that:

‘Waste management in England has come a long way over the last 10 years: waste going to landfill has nearly halved since 2000; household recycling rates have climbed to 40%; waste generated by businesses declined by 29% in the six years to 2009 and business recycling rates are above 50%. But we need to go further’

‘Given the picture of material resource use in England, it is clearly wrong that we still send so much material to landfill in England that is a potential resource. While the overall volume of waste disposed of in landfill has reduced at a significant rate in recent years – a 45% fall since 2000/01 – in 2009 we still landfilled 44 million tonnes of waste in this country. Our vision for the zero waste economy is that landfill should be the waste management option of last resort and only for wastes where there is no better use.’

United States of Recycling

In this series, America has been mentioned a fair amount, so it’s important to make reference to their efforts. The ‘Municipal Solid Waste Generation, Recycling, and Disposal in the United States: Facts and Figures for 2010’ states that 136 million tons (tonnes) of MSW was sent to landfill in 2010. That’s 136 million tonnes equates to 54.1% of the total waste, with 34.1% being recycled or recovered and the remaining 11.7% being combusted for energy.

America logged 85.1 million tonnes of material being recycled in 2010, up from 69.5 million in 2000, a staggering increase. This was also a 5.5% increase in the percent recycled from total waste.

The 2000s and Beyond: Growth Of Recycling

The end of the Noughties wasn’t all that long ago, but it sure feels that way. In the same year of the Haiti earthquake disaster, the Chilean miners, the Wikileaks scandal and the first African world cup, a decade of successful recycling initiatives bore fruition and the recycling reviews were all positive and deserve plaudit.

It’s now 2014 and we still haven’t named this decade, since a clear name is not forthcoming. Suggestions include tens, tennies, tenties and teenies but I’ve come across a much more optimistic answer. The one-ders. This is in hope that this decade with provide numerous breakthroughs in all fields of science, politics and the environment.

It is hoped that recycling rates will only continue to increase, and we work hard towards the zero waste target of 2020.